“Sir, my mother has a tattoo just like yours,” I say to the billionaire while I’m waiting tables in Midtown Manhattan, and the second the words leave my mouth, I know I’ve crossed a line no New York server is supposed to cross—especially not with him.

I work as a waitress at one of the most expensive Italian restaurants in New York City. The leather banquettes are softer than my mattress at home in Brooklyn, the chandeliers look like they were stolen from a Fifth Avenue hotel, and one bottle of Barolo can cost more than our monthly rent. Most nights I serve celebrities, Wall Street guys, CEOs, tech bros, people who spend more on a single meal than I make in a week.

I smile. I’m professional. I keep my voice soft and my posture straight. I don’t ask for autographs. I don’t gush. I don’t make a scene. In this part of Manhattan, silence and discretion are part of the uniform.

Three months ago, on a cold Friday night in late October, I was eight hours into a double at Cipriani Downtown. Outside, Broadway was a blur of yellow cabs, honking horns, and steam rising from manholes. Inside, everything was polished wood, white tablecloths, the clink of crystal, the low hum of Frank Sinatra over the sound system.

It was one of those nights when every table was triple‑booked and my feet felt like they were made of glass. I smelled like truffle butter, espresso, and whatever perfume the last customer wore. My ponytail was coming loose. My smile felt stapled onto my face.

That’s when Adrien Keller walked in.

If you don’t know the name, you’ve probably used something he built. He’s worth $4.2 billion—tech mogul, self‑made German immigrant, the kind of man who shows up on every Forbes and Fortune list with headlines like THE GHOST KING OF SILICON VALLEY and THE BILLIONAIRE WHO HATES SPOTLIGHTS.

He made his money in software—code that lives quietly on people’s phones from Brooklyn to Boise, running their lives in the background. I’d seen his face on magazine covers at the bodega near our apartment in Brooklyn. I’d scrolled past his interviews on YouTube while waiting for laundry to dry in a coin‑op on Atlantic Avenue.

I never expected him to be sitting alone at one of my tables.

He came in without an entourage. No security guards, no PR person, no model on his arm. Just a man in a charcoal suit and an open‑collared white shirt, shoulders slightly bowed, walking through the revolving door like he hoped no one would notice.

He still drew every eye in the room.

Josh, the floor manager, caught my sleeve as I passed the bar with a tray of empty martini glasses.

“Lucia, table twelve,” he murmured. “VIP. He asked for privacy and the best server we have. That’s you.”

“Who is it?” I asked, shifting the tray on my shoulder.

Josh’s eyes flicked toward the private corner table, the one tucked against the exposed brick with a view of the Hudson and the West Side Highway lights.

“Adrien Keller,” he said, like he was dropping a bomb.

My stomach dipped.

Everyone in New York knew that name.

I dropped the glasses at the service station, grabbed a polished water pitcher, took a breath, and walked toward table twelve. The restaurant noise softened in my ears, like someone had turned down the volume.

Adrien sat with his back to the wall, the way I’d seen cops and ex‑military guys sit on the subway. Mid‑forties, maybe. Dark blond hair threaded with gray at the temples. Clean‑shaven, strong jaw, a faint scar near his right eyebrow that the magazines never mentioned. No flashy watch. No obvious logo. Just a man in a very good suit who could buy the entire block if he felt like it.

He was staring down at his phone, the blue light painting the edges of his face. Up close, the thing that struck me wasn’t his money.

It was that he looked lonely.

Not the performative, Instagram kind of loneliness. Real loneliness. That quiet, heavy kind that hangs around people who’ve lost something they don’t know how to get back.

I pasted on my Cipriani smile.

“Good evening, sir,” I said softly. “My name is Lucia, and I’ll be taking care of you tonight. Can I start you with something to drink?”

He lifted his head.

His eyes were a pale winter blue, the color of the sky over the East River in January. Sharp. Tired. Like he hadn’t slept properly in years.

“Red wine,” he said. His accent was faint but there, German rounded off by twenty‑plus years in New York. “Whatever you recommend.”

“The Bordeaux is excellent,” I said. “Full‑bodied, smooth finish. It pairs with most of our mains.”

“That’s fine,” he said. “Thank you.”

I poured water. I set down bread and olive oil. I recited the specials I could say in my sleep: Wagyu carpaccio, lobster ravioli, truffle risotto. He ordered a filet mignon, medium rare, with asparagus. Simple. No substitutions. No fuss.

For a man whose net worth had more zeros than I could process, he ordered like any tired Midtown guy grabbing dinner after a long day.

“I’ll have that out shortly,” I said.

I turned to leave. That’s when I saw it.

His left hand rested on the white linen tablecloth, fingers long and square‑tipped, knuckles nicked like there had once been a time when he swung a hammer instead of signing deals. His shirt cuff had ridden up just half an inch.

And there, on the inside of his wrist, was a tattoo.

Small. Delicate. Inked in red and black.

A single red rose, its stem wrapped in sharp black thorns. The thorns twisted around themselves to form the shape of an infinity symbol, looping back and around, no beginning, no end.

For a second, my brain refused to connect what my eyes were seeing.

Then my heart slammed against my ribs so hard I nearly dropped the water pitcher.

I knew that tattoo.

I had grown up watching that exact rose move across my mother’s wrist. I’d seen it when she stirred simmering tomato sauce in our cramped Brooklyn kitchen, when she buttoned my worn coat on snow days, when she hugged me after bad tests and broken friendships. Faded red petals. Black thorns forming a sideways eight.

Same design. Same size. Same placement.

Left wrist. Inside.

My mother’s tattoo was twenty‑something years old now. The red had softened, the black lines blurred a little. Years of bleach, cleaning chemicals, New York winters, and hard work had worn it down. But it was the same tattoo.

I remember being seven years old, sitting on our secondhand couch in our walk‑up off Atlantic Avenue, watching Saturday morning cartoons while my mother folded laundry. Her wrist moved in front of my face and my eyes caught on the rose.

“Mama, what does that mean?” I’d asked, grabbing her hand.

She’d glanced down at the ink, then at me. For a moment something flashed in her face—pain, maybe, or memory. Then she’d smiled.

“It’s from a long time ago, tesoro,” she’d said, using the Italian pet name she saved for the softest moments. “Before you were born.”

“But what does it mean?” I’d insisted.

She’d run a thumb gently over the rose.

“It means love is beautiful,” she’d said. “But it hurts. And it lasts forever.”

“Did you love someone?” I asked.

“I love you,” she said immediately.

“I mean someone else,” I said, stubborn.

Her smile turned sad around the edges.

“Once,” she said. “A long time ago.”

“Was it my dad?” I asked, the way kids ask questions they don’t know are explosive.

Her eyes went distant.

“He’s gone, tesoro,” she said. “That’s all. Now go play.”

After that, every time I brought it up, she would change the subject. Eventually, I stopped asking out loud.

But I never stopped wondering.

And now, standing in a Manhattan restaurant where a single plate of pasta could pay our electric bill for a month, I was staring at the exact same tattoo on the wrist of a billionaire I’d never met.

My throat went dry.

The room seemed to narrow until all I could see was that rose, that infinity symbol, the faint flutter of a blue vein under his skin.

He must have felt my stare. His fingers stilled on the tablecloth. His gaze lifted from his phone.

“Is something wrong?” he asked.

I realized I’d been frozen in place for a full three seconds—an eternity in New York restaurant time.

“I… I’m sorry,” I stammered, heat flooding my cheeks. “I shouldn’t say anything. It’s not professional.”

My manager’s voice echoed in my head. Don’t get personal. Don’t cross lines. You are invisible until they need something.

I should have walked away, gone back to the kitchen, pretended the world hadn’t just tilted sideways.

Instead, the words broke free before I could stop them.

“This is going to sound crazy,” I said, my voice shaking, “but my mother has a tattoo exactly like that. Same rose, same thorns, same wrist.”

For a second, nothing happened.

Then everything did.

Every muscle in his body seemed to lock. His wineglass paused halfway to his lips, a drop of dark red clinging to the rim.

“What did you say?” he asked quietly.

“My mother,” I repeated, my palms slick around the water pitcher. “She has that exact tattoo. I’ve asked her about it my whole life. She never tells me what it means. She just says it’s from before I was born.”

His voice, when it came, sounded like it had scraped against something jagged on the way out.

“What is your mother’s name?”

“Julia,” I said. “Julia Rosi.”

For a heartbeat, the entire restaurant disappeared—every candlelight reflection on wineglasses, every clink of silverware, every Sinatra lyric drifting through the air.

He stared at me like I’d crawled out of his past.

“Why do you—” I started.

The stem of the wineglass slid from his fingers.

It hit the edge of his plate, shattered, and red wine exploded across the pristine white tablecloth, spreading like blood. Shards of crystal skittered across the linen.

“Julia,” he whispered.

People at neighboring tables glanced over, half curious, half annoyed. Accidents were supposed to happen at the cheap bars downtown, not here.

“I’m so sorry, sir,” I said automatically, dropping to grab napkins, my heart pounding. “Let me get you another glass, I’ll clean this up—”

“How old are you?” he asked.

He wasn’t looking at the mess. He was looking at me like everything suddenly depended on my answer.

“Twenty‑four,” I said. “I’m twenty‑four.”

He went still in a different way. Not shock this time. Calculation. Memory.

“Are you okay?” I asked. “Do you… want to sit down? I can get the manager—”

“Twenty‑four,” he repeated, so softly I barely heard it over the low music.

His gaze slid past me to the city visible through the window: the shimmer of downtown lights, the moving dots of cabs on the West Side Highway. Then it returned to my face.

“Where is she?” he asked. “Where is Julia?”

“She’s in the hospital,” I said, the words catching. “She’s sick.” I swallowed. “Do you… know my mother?”

His chair scraped back as he stood up so fast it almost toppled.

He pulled out his wallet and fanned out crisp bills like a magician dealing cards. Five hundred‑dollar bills hit the tablecloth, soaking up the wine.

“I have to go,” he said.

“Wait, your food—”

“Keep the money,” he said. “I have to go.”

He was already moving, slipping his wallet back into his jacket, cutting through the restaurant with long strides. Heads turned as he passed, but no one stopped him. The host swung the door open, cold October air burst in, and then he was out on the sidewalk, swallowed up by New York.

I stood there staring at the empty chair, at the blood‑red stain seeping across the tablecloth, at the five hundred dollars lying there like Monopoly money.

I had no idea that in less than twenty‑four hours, my entire life story would be rewritten.

Before we go further, let me ask you something.

Have you ever learned a secret about your parents that made your whole childhood tilt, like a subway car lurching around a corner? Something that didn’t just change what you knew about them… it changed what you knew about yourself?

If you have, I want you to hold that feeling in your hands while I tell you the rest of this story.

Because that’s what happened next.

The first thing you need to know is this:

My mother is dying.

She has breast cancer. Stage four. By the time they caught it at a clinic on the Upper East Side, under fluorescent lights that made everyone look already ghostly, it had already spread to her lymph nodes and her liver.

The oncologist sat across from us, hands folded, charts on the screen behind him. Outside, yellow cabs honked on Fifth Avenue. Inside, time slowed to a crawl.

“With aggressive treatment,” he said, “maybe a year.”

That was three months ago.

Since then, my mother has been fighting with everything she has—chemotherapy, radiation, a trial drug that made her skin peel and her bones ache. We have memorized the subway transfers between Brooklyn and the hospital. We have learned the names of nurses and the taste of awful hospital coffee.

Even with insurance, the bills are brutal. Deductibles. Co‑pays. Medications that cost more than my monthly salary.

My mother, Julia, has spent the last twenty‑four years cleaning other people’s homes in Manhattan and Brooklyn. She scrubs marble counters in Park Slope brownstones, vacuums white carpets in Tribeca lofts, polishes chrome fixtures in penthouses overlooking Central Park.

Six days a week, sometimes seven. She leaves our apartment before sunrise with a thermos of coffee and a plastic bag of cleaning supplies, rides the subway with nurses and construction workers, gets off in neighborhoods where the dogs wear sweaters and the doormen call her “Miss” but never bother with her last name.

She never complains. Never takes a day off unless she’s too sick to stand. She just works and works and works so I could have school supplies, secondhand winter coats, and the occasional birthday cake from the Italian bakery on Court Street.

Then the cancer knocked her off her feet.

She can’t work anymore. Some days she can barely walk from the couch to the kitchen.

So I work.

I work double shifts at Cipriani. Breakfast and dinner, sometimes lunch if they’re short‑staffed. I lace up my black non‑slip shoes while it’s still dark outside, ride the F train into Manhattan with my earbuds in and my stomach empty, change into my uniform in the employee locker room, and plaster on that smile.

On a good night, if the tips are generous and no one decides I’m invisible, I bring home four hundred dollars in cash. It sounds like a lot until I look at the stack of envelopes on our chipped kitchen table—hospital bills, lab fees, notices stamped in red.

It’s not enough.

But it’s all I have.

The night Adrien came in was one of those nights when New York felt like a movie set and I felt like an extra. The restaurant buzzed with people who smelled like expensive cologne and success. Outside, the Hudson River reflected the city lights like something out of a postcard.

By the time his wineglass shattered, I was already exhausted, already counting down the hours until I could sink into the sagging mattress in my tiny bedroom.

I finished my shift in a daze, my mind looping around the same questions.

How did a billionaire in Manhattan have the same tattoo as my mother?

How did he know her name?

Why did he look like I’d thrown him off a building when I said it?

By the time I clocked out, took the subway back to Brooklyn, and climbed the stairs to our third‑floor walk‑up, it was nearly 2 a.m. The hallway smelled like someone’s overcooked dinner and industrial cleaner.

I kicked off my shoes, sank onto our saggy couch, and stared at the water stain on the ceiling.

Then I pulled out my phone.

Me: Mama, do you know someone named Adrien Keller?

I watched the typing dots that never appeared.

She was probably asleep. The medication makes her sleep hard and deep, like she’s sunk underwater.

So I did what people do when they’re scared and curious in the middle of the night.

I Googled him.

Article after article filled my screen. Forbes, Bloomberg, TechCrunch. Posed portraits in crisp suits. Candid shots of him stepping out of black SUVs on Fifth Avenue. Photos from conferences in San Francisco, speaking under bright lights about algorithms and disruption.

In every picture, he looked controlled. Composed. Alone.

There were no wedding photos. No shots of him with kids. No rings on his fingers.

A headline caught my eye: TECH’S MOST ELIGIBLE BACHELOR: WHY HASN’T ADRIEN KELLER SETTLED DOWN?

I clicked.

Near the end of the article, buried between questions about IPOs and philanthropy, there it was.

“I was in love once,” he said after a long pause. “A long time ago. It didn’t work out. I’ve never found that again.”

My heart beat so loud I could hear it in my ears.

In one photo embedded in the article, his shirt cuff had ridden up just enough to show the edge of the tattoo. Red petals. A dark curve of thorn.

I stared at the image until my vision blurred.

What happened between him and my mother?

The next morning, I took the 4 train uptown to Mount Sinai. I knew the ride by heart now: transfer at 14th, gray faces in the train car, the jerk of the subway as it climbed onto the elevated tracks for a minute before diving back underground.

It was a bright, cold Saturday. Central Park trees were halfway between green and bare, their leaves burnt orange and gold. Joggers moved along the paths, bundled in leggings and tech fabric. On Fifth Avenue, tourists took pictures of the museum steps.

The oncology wing did not care what the weather was doing outside.

My mother was in room 407. The hallway smelled like bleach and something metallic. A TV in the waiting room played muted cable news no one was watching.

She was awake, sitting up in bed when I walked in, a paperback folded open on her lap. The chemotherapy had taken her hair, leaving her scalp covered with a soft scarf patterned with tiny blue flowers. Her face looked thinner, her collarbones sharper, but her eyes—deep, dark brown—still lit when she saw me.

“Tesoro,” she said, smiling. “You didn’t have to come so early.”

“I always come on Saturdays,” I said, leaning down to kiss her forehead. Her skin felt warmer than it should. “How are you feeling?”

“Tired. A little nauseous.” She shrugged one thin shoulder. “The usual.”

We talked for a while about everything and nothing—how the nurse with the purple braids had smuggled in real coffee, how the volunteer at the front desk wore too much cologne, how the woman in the room next door kept watching the same game show on repeat.

Then I asked it.

As casually as someone stepping off a cliff.

“Mama,” I said, pretending to straighten her blanket, “do you know someone named… Adrien Keller?”

Everything in her went still.

Her fingers froze around the book. Her smile slipped.

“Why do you ask that name?” she whispered.

“He came into the restaurant last night,” I said. “He has a tattoo on his wrist exactly like yours. Same rose. Same thorns. Same place.”

The color drained from her face so fast I thought she might pass out.

“Adrien was there?” she breathed. “At your restaurant?”

So she did know him.

“You do know him,” I said.

“He is… famous,” she said absently, as if she had forgotten who he was to the rest of the world and remembered only who he had been to her. “Lucia, where is he now?”

“I don’t know,” I admitted. “He left. He saw me, asked your name, and when I said ‘Julia Rosi,’ he dropped his glass and walked out.”

Her eyes filled with tears so quickly it hurt to watch.

“He found me,” she choked out. “After all these years, he found me.”

“Mama, who is he?” I asked.

She swallowed hard, her gaze never leaving my face.

“I knew him as Adrien Keller,” she said slowly. “But back then he was just Adrien. No company. No billions. He worked construction in the East Village. He came to this country with nothing and lived in a little apartment with peeling paint and three roommates. We were young. Stupid. In love.”

The word hung in the air between us.

“What happened?” I asked.

“I had to leave,” she said. “My nonna in Italy had a stroke. My mother called and said it was bad. I had to go back. I promised Adrien I would return in six months.”

She looked down at her wrist, at the faded rose.

“The week before I left, we went to a tiny tattoo shop above a bodega in the East Village. August in New York. Hot. The kind of sticky heat where the city smells like garbage and opportunity.”

Her lips trembled into the ghost of a smile.

“He said, ‘Even if we are on different continents, we will have this. Proof that we existed. That what we had was real.’ So we both got the rose. The thorns as infinity.”

Her fingers brushed the ink. Her eyes shone.

“And then?” I asked.

“And then I left,” she said. “I flew to Italy. I held Nonna’s hand in a hospital that smelled like lemons and disinfectant. I told her about New York. About Adrien. I thought I had time.”

Her voice went quieter.

“I found out I was pregnant about a month after I arrived,” she said. “Six weeks along.”

“With me,” I said.

“With you,” she said, and despite everything, her face softened. “I wanted to tell him. I tried to call, but international calls were so expensive, and the line never connected. I wrote letters and sent them to his address. I do not know if they ever arrived. I kept telling myself, ‘I will tell him when I go back. I will tell him in person.’”

“But when you came back, he was gone,” I said, already knowing.

“I was seven months pregnant,” she said. “Huge. I went to his building in the East Village. The landlord said he had moved in December. No forwarding address. Phone disconnected.”

She shook her head, a small, helpless gesture.

“I looked for him for two weeks,” she said. “I asked everyone I could find who knew him. No one had an answer. I could barely walk up the subway stairs. My feet were so swollen.”

She blinked back tears.

“After two weeks, I gave up,” she whispered. “I told myself if he wanted to find me, he would. Maybe he had changed his mind. Maybe he had met someone else. I needed to focus on you. On keeping you safe.”

She glanced at me, fear and guilt and love all tangled in her eyes.

“So when you asked about your father,” she said, “I told you he was a man from Italy who left. It was easier than telling you he was here somewhere, in the same city, and I just… could not find him.”

I sat there, trying to process twenty‑five years of silence.

“I am so sorry, tesoro,” she whispered. “I should have told you sooner. I should have—”

“Mama,” I said, leaning forward, taking her hand. Her skin felt fragile under my fingers. “I’m not angry at you. I’m just… sad. Sad for you. Sad for him. Sad for all the years we lost.”

“You’re not angry?” she asked, her voice small in a way I’d never heard.

“How could I be?” I said. “You were twenty‑three, alone, pregnant, and scared in a city that barely noticed you. You did the best you could. You gave me everything. You worked yourself half to death so I could have a life.”

Her shoulders shook with quiet sobs.

“You deserved a father,” she said. “And he deserved to know he had a daughter.”

“You both deserved better timing,” I said softly. “You were both looking. You just kept missing each other.”

She wiped her eyes with the back of her hand.

“I need to see him,” she said suddenly. “Lucia, please. I need him to know I never forgot.”

“I don’t have his number,” I said. “I don’t even know how to contact him. But… he’s famous. There has to be a way.”

I squeezed her hand.

“I’ll try,” I said. “I promise.”

I stepped into the hallway and called the restaurant.

“Cipriani Downtown,” Josh answered, the clatter of lunch prep in the background.

“Hey, it’s Lucia,” I said. “Did Mr. Keller leave any contact info last night? A card, an email, anything?”

“No,” Josh said. “But, uh… Lucia? Someone’s here asking for you.”

My heart stuttered.

“Who?”

“He says his name is Thomas Beck. He’s Adrien Keller’s lawyer. He wants to talk to you.”

Of course he had a lawyer.

“I’m at Mount Sinai with my mom,” I said. “Can he come here?”

“Hold on,” Josh said.

Muffled voices. A clatter of plates.

“He says he’ll be there in thirty minutes,” Josh said.

Thirty minutes in New York can be an eternity or a heartbeat. That day, it felt like both.

Thomas Beck found me in the hospital cafeteria, sitting at a table sticky with dried coffee rings.

He was in his fifties, wearing a charcoal suit that fit almost as well as Adrien’s but with less effortless ease. His gray hair was neatly barbered, his tie precisely knotted. He had the air of someone whose phone never stopped buzzing.

“Ms. Rosi?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said, standing.

He shook my hand, introduced himself, and sat across from me.

“I represent Mr. Keller,” he said. “He asked me to find you and to ask about your mother.”

“Is he okay?” I blurted. “He seemed… I don’t know. Not okay last night.”

A tired half‑smile touched Thomas’s mouth.

“He hasn’t been okay in twenty‑five years,” he said. “Last night was the first time I’ve seen something like hope on his face in a very long time.”

He pulled out a tablet and opened a blank document.

“Can you tell me about your mother?” he asked. “Her full name, age, medical condition.”

“Julia Rossi,” I said. “Forty‑eight. Stage‑four breast cancer with metastasis to the liver and lymph nodes. She’s in room 407.”

He typed quickly.

“And you said she knows Mr. Keller,” he said.

“She says they were in love twenty‑five years ago,” I said. “She had to go back to Italy. She promised she’d come back in six months. When she did, he was gone. She looked for him. She thought he’d moved on.”

Thomas let out a breath through his nose.

“He didn’t move on,” he said. “He spent the next five years looking for her. He thought she’d stayed in Italy. He thought she’d chosen her family.”

My chest clenched.

“So they both thought the other left,” I said.

“Yes,” Thomas said simply.

He closed the tablet.

“Adrien wants to see her,” he said. “With your permission.”

“She wants to see him,” I said. “More than anything. When?”

“Today,” he said. “Now, if possible. I understand her condition is… serious.”

“She doesn’t have time to wait,” I said.

“Then we won’t make her wait,” he said.

Three hours later, there was a knock on the door of room 407.

I opened it.

Adrien stood in the doorway in the same charcoal suit from the night before, but something in his posture had changed. The armor he wore in photographs—the billionaire cool, the distance—had cracked. He looked older. Raw.

“Is she…?” he started.

“She’s awake,” I said. “She knows you’re coming.”

I hesitated.

“But Adrien?” I added.

He met my eyes.

“She’s very sick,” I said. “She doesn’t look like she did back then. The chemo…”

He shook his head.

“I don’t care,” he said. “I just need to see her.”

I stepped aside.

He walked past me into the room.

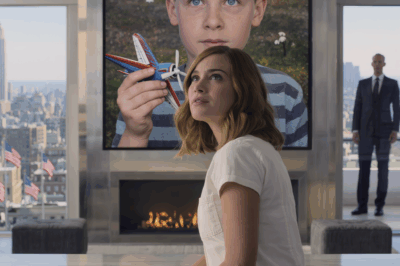

My mother was sitting up, hands folded in her lap, eyes locked on the doorway. For a second, the fluorescent lights seemed softer, like the city itself was holding its breath.

“Adrien,” she whispered.

“Julia,” he said.

Twenty‑five years collapsed in an instant.

He crossed to her bed and took her hand. His fingers trembled as they traced the faded rose on her wrist. She reached up with her free hand and touched his face like she was making sure he was real.

Neither of them spoke.

Then they both started to cry.

I backed out of the room and pulled the door closed, giving them privacy.

For the next two hours and seven minutes—yes, I checked the time—I sat on a hard plastic chair in the corridor. Nurses walked by, pushing carts. A janitor mopped the floor. A kid down the hall cried. An overhead announcement mentioned a code I didn’t understand.

Every so often, I heard muffled voices from behind the door. Then silence. Then the kind of laughter that sounded like it hurt.

I stared at the ceiling. I scrolled through my phone without seeing anything. I tried to imagine everything they were saying, everything they were trying to cram into such a short time.

When the door finally opened, I stood so fast my legs nearly buckled.

Adrien stepped out.

His eyes were red. His face was pale. He looked like someone had taken him apart and put him back together in a slightly different order.

“Is she okay?” I blurted. “Is my mother—”

“She’s okay,” he said. “She’s…”

He stopped.

Then he looked at me. Really looked at me. Not like I was a waitress or a stranger or a problem to solve.

Like I was a question he’d been trying to answer for twenty‑five years.

“You’re scaring me,” I said. “What did my mother tell you?”

“Lucia,” he said quietly. “I need to talk to you. Somewhere private.”

“The cafeteria?” I suggested, heart pounding.

He nodded.

We walked there in silence.

The cafeteria was half full of families clutching paper cups, doctors wolfing down sandwiches, nurses staring at their phones. We got coffee from the machine on autopilot and took a table in the corner, under flickering fluorescent lights.

Neither of us touched our cups.

“Okay,” I said. “What did she say?”

He didn’t answer that.

Instead, he asked, “When is your birthday?”

“What?”

“Your birthday,” he repeated, his voice too calm. “The date.”

“March fifteenth,” I said slowly.

“What year?”

“Two thousand,” I said. “Why?”

He closed his eyes for a second, like he was bracing for impact.

“When your mother went back to Italy in 1999,” he said, “she didn’t know she was pregnant. She found out in August. She told me that just now.”

The world narrowed to the sound of his voice.

“She was pregnant with you, Lucia,” he said. “She came back to New York in January 2000, seven months along. She went to my old apartment. I wasn’t there. I’d moved in December. She spent two weeks looking for me. Then, on March fifteenth, you were born in this hospital. She was completely alone.”

My fingers tightened around the cardboard cup.

“Are you saying…?” I couldn’t make myself finish.

“I’m saying,” he said, “we think I’m your father.”

The floor dropped out from under me.

The cafeteria noise turned into a distant roar. A TV blared weather in Times Square. Somewhere a child laughed. My vision tunneled.

“No,” I said, shaking my head. “No. My mother told me my father was someone from Italy. She said he left.”

“She said that because she couldn’t find me,” he said. “She thought I’d moved on. She thought I’d chosen something else. But I was here, Lucia. I was in New York the entire time. I just didn’t know.”

“You didn’t know about me,” I whispered.

He flinched.

“I had no idea,” he said. “If I had known—if I had found her when she came back—everything would have been different. I would have been there. At the hospital. In the apartment. For… all of it.”

Tears burned the backs of my eyes. Anger, grief, disbelief, longing—everything crashed together.

“I need to hear this from her,” I said, standing abruptly. The chair screeched across the tile. “I need to hear it from my mother.”

I walked back to room 407 with my pulse pounding.

My mother looked up when I came in. Her cheeks were wet. Her scarf was slightly askew.

“He told you,” she said quietly.

“Yeah,” I said, dragging the chair closer to her bed. “He told me.”

“Are you angry?” she asked.

“I don’t know what I am,” I said honestly. “I feel like someone picked up my life and shook it.”

I took a breath.

“Tell me everything,” I said. “From the beginning. I need to understand.”

So she did.

She told me about meeting Adrien in 1999 in a building on Avenue B, both of them working under the table—her cleaning apartments, him doing drywall and painting. About sharing bad coffee at a twenty‑four‑hour diner on Houston because they couldn’t afford anything else. About walking over the Williamsburg Bridge at sunrise, talking about the kind of futures they wanted.

She told me how he’d confessed his dream of working with computers, of building something that would outlast him. How she’d told him about growing up in a tiny town near Naples, watching American movies and promising herself she’d live in New York one day.

She told me about cheap dates in Washington Square Park, kissing on street corners in the East Village, falling asleep in each other’s arms in a tiny apartment that smelled like paint and garlic.

She told me about the phone call from Italy, about Nonna’s stroke, about the overnight flight back to a country that no longer felt like home.

“I thought it would be six months,” she said. “I thought I would come back and nothing would have changed.”

She told me about finding out she was pregnant, about hearing my heartbeat on a scratchy ultrasound machine in Naples, about crying on a plastic chair in the hospital waiting room because she wanted Adrien to be there.

“I tried to call,” she said. “The line never worked. I wrote letters. I don’t know if he ever received them. Phone cards, post offices, addresses—I did not know what I was doing. I kept thinking, ‘When I go back to New York, I will fix this. I will find him.’”

She told me about the landlord in the East Village shrugging, saying he’d moved out, no forwarding information. About searching the neighborhood with swollen ankles, asking at the corner deli, the laundromat, the construction sites.

“And after two weeks,” she said, “I was so tired. So scared. I had you to think about. So I stopped. I told myself, ‘He left. That is all.’”

She looked at me, raw.

“I am so sorry,” she whispered again.

“I meant what I said,” I told her. “I’m not angry. I’m just heartbroken for all of us.”

Her shoulders sagged with relief and grief.

“I love you so much, tesoro,” she said.

“I love you too,” I said.

After a while, I stepped into the stairwell because it was the only place in the hospital that felt unobserved. The air was cooler there, tinged with dust and the faint scent of mop water.

I didn’t go there to cry. I went to breathe.

Adrien found me sitting on the concrete steps, elbows on my knees.

“May I sit?” he asked.

I nodded.

He sat beside me, leaving a careful space between us.

“Your mother told you everything?” he asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “And I get it now. The missed calls. The landlord. The timing. It wasn’t some big betrayal. It was just… life. Being cruel.”

He let out a humorless breath.

“That’s one word for it,” he said.

“I do have one question,” I said. “Why did you move in December? Right before she came back?”

He rested his forearms on his knees, hands clasped.

“I got a job offer,” he said. “A startup in Midtown. They needed someone who could code, even if he’d learned it in a public library instead of a fancy school.”

He stared down at his hands.

“It was more money than I’d ever seen,” he said. “Enough that I thought, ‘If I work like hell for a year, I can save enough to go to Italy. To find Julia. To do this right.’ So I moved closer to the office. Tiny apartment. New number. New schedule. I told the landlord, ‘If a young woman named Julia comes looking for me, give her my number.’”

He gave a small, bitter smile.

“He was eighty‑nine,” Adrien said. “I shouldn’t have trusted his memory.”

“Mom said she asked him,” I said. “He told her you didn’t leave anything.”

Adrien nodded once.

“I moved in early December,” he said. “Started the job December fifteenth. Your mother says she came back January tenth.”

“One month,” I said.

“One month,” he echoed. “If I’d waited. If she’d come sooner. If the landlord had written down my number instead of trusting his brain…” He shook his head. “I have replayed that month in my mind for twenty‑five years.”

“You were trying to build a better life for her,” I said quietly. “For both of you.”

“And instead, I missed the moment that mattered most,” he said.

We sat in silence for a while, listening to the muted thump of footsteps on the stairs above us.

“So,” I said eventually, “do you want to do a DNA test?”

“Yes,” he said immediately. “I think we both know what it will say. But I need it confirmed. For legal reasons. For medical reasons. And because…”

He broke off.

“And because?” I prompted.

“Because if I let myself believe you’re my daughter,” he said slowly, “and it turns out you’re not, I don’t know what that would do to me.”

Something in my chest cracked.

“Okay,” I said. “We’ll do the test.”

He looked almost startled, then relieved.

“Thank you,” he said.

The hospital moved fast once Adrien’s name was attached to the request. Blood draws, paperwork, lab orders marked STAT. Money moves things in this city in a way nothing else does.

Three days later, my phone buzzed.

Adrien: The results are in. Can you come to the hospital? I want us all together when we read them.

Me: I’ll be there in 30.

When I reached the oncology floor, he was waiting outside my mother’s room, an envelope in his hand. For once, his fingers weren’t shaking.

“Ready?” he asked.

“No,” I said. “But do it anyway.”

He smiled faintly.

We went in.

My mother sat up straighter, eyes glued to the envelope.

Adrien opened it with careful fingers, unfolded the top page, and scanned it. For a second, he just stared.

Then he looked at me.

“‘Probability of paternity: 99.9 percent,’” he read.

My knees went weak.

“Lucia,” he said, and his voice did that breaking thing again. “You’re my daughter.”

My mother let out a sound that was half sob, half laugh. Her hand flew to her mouth.

“Oh my God,” I whispered.

“Come here, tesoro,” my mother said, holding out her arms.

I went to her and she pulled me in, her arms surprisingly strong around my shoulders. I cried into her hospital gown, feeling her heart hammering against my cheek.

When I looked up, Adrien was standing there like he wasn’t sure if he was allowed to move.

“You can come too,” I said.

Something broke in his face.

He stepped forward and wrapped his arms around both of us. For the first time in twenty‑four years, we fit into a shape we should have been in all along.

“What happens now?” I asked when we finally pulled apart, my voice hoarse.

Adrien looked at my mother, then at me.

“Now I fix this,” he said. “As much as I can. I can’t go back. But I can be here now.”

Things changed quickly after that, the way weather changes in New York—slowly for a long time and then all at once.

My mother’s oncologist, Dr. Daniela Hill, called me into her office. It was a cramped space with overflowing folders, a dying plant on the windowsill, and a postcard of the Brooklyn Bridge pinned above her computer.

“Ms. Rossi,” she said, pushing her glasses up her nose. “I received a call from someone claiming to be a representative of Mr. Keller. He wants to transfer your mother to Memorial Sloan Kettering. Private room. Access to clinical trials. He told me there is no budget limit.”

She paused.

“Is this real?” she asked. “Is this something you and your mother want?”

“Yes,” I said. “It’s real. And yes, it’s what we want. We can’t afford any of this on our own.”

Dr. Hill’s expression softened.

“In that case,” she said, “I’ll make the calls. There’s an immunotherapy trial at Sloan Kettering that I’ve been trying to get her into. It’s promising. It’s also very expensive, and insurance doesn’t touch it.”

“Money isn’t the problem anymore,” I said, the sentence feeling strange and new in my mouth.

Within days, my mother was moved to Sloan Kettering on the Upper East Side. The new room was bigger, brighter, with a view of the East River where tugboats moved like toys. The nurses had time to smile. The machines were newer. The food was marginally less terrible.

Adrien paid for everything.

He also paid off her existing medical debt—over $140,000 in past‑due bills and collection notices that had been living in a shoebox under our sink.

One afternoon, he handed me a folder in the hospital cafeteria.

Inside were documents showing my rent paid for the next year.

“I want you to quit the restaurant for now,” he said. “Go back to school. Finish your degree.”

“I dropped out of NYU when she got sick,” I said. “I couldn’t afford tuition and her treatments.”

“Go back,” he said simply. “We’ll cover it. Your mother wants you to finish. So do I.”

“It’s too much,” I said automatically.

“It’s not enough,” he said. “It’s twenty‑four years late.”

Over the next few months, I watched something I hadn’t seen in a very long time.

I watched my mother fall in love again with the same man.

And I watched him fall in love with both of us.

Adrien visited every day. Sometimes he came straight from his office in a glass tower in Midtown, tie loosened, laptop bag still on his shoulder. Sometimes he showed up in jeans and a sweater, eyes shadowed but soft.

He would sit by her bed for hours, holding her hand, talking in low voices. They caught up on everything they’d missed: the early days of his startup, the nights he slept under his desk, the first time he saw his company’s name scroll across the Nasdaq ticker in Times Square. The day my mother felt me kick for the first time on a crowded bus in Naples. My first day of kindergarten in Brooklyn. The way he’d walked past playgrounds in the East Village wondering if any of the kids were his.

“We lived in the same city for twenty‑five years,” my mother said one afternoon, shaking her head in disbelief. “All that time.”

“Until Lucia,” Adrien said.

They both looked at me.

I was sitting in the corner chair pretending to read, but my chest ached.

“She saved us,” my mother said. “Our daughter saved us.”

The immunotherapy started working.

Not like magic. Not like a commercial. My mother was still tired, still nauseous, still living in a body that had been through hell.

But three months into the trial, her new oncologist pulled up her scans and smiled.

“The tumors are shrinking,” he said, tapping the screen. “Not gone. But smaller. We’re calling this a remission.”

My mother burst into tears.

So did I.

So did Adrien, quietly, turning his face away for a second like he’d forgotten he was allowed to show that kind of vulnerability.

“How long?” my mother asked, wiping her cheeks. “Really. How much time?”

“I can’t promise anything,” the doctor said. “But with continued treatment, we’re talking years. Not months.”

“Years,” my mother repeated.

She looked at Adrien, eyes bright.

“We have years,” she whispered.

“We have whatever time you’ll give me,” he said.

Six months after the night his wineglass shattered in my section, Adrien proposed.

Not at a rooftop restaurant or on a private jet. Not with a choreographed flash mob or fireworks over the East River.

He proposed in her hospital room on a Tuesday afternoon while the city outside kept doing what it always does—honking, rushing, never stopping.

He came in wearing a navy suit and no tie, his hair mussed like he’d been running his hands through it. My mother was sitting up in bed, a knit blanket from some volunteer charity draped over her legs.

“I should have done this twenty‑five years ago,” he said, standing at the foot of her bed. “I should have taken you to City Hall the day you got that tattoo and not let you on that plane to Italy.”

My mother laughed softly, already crying.

“I was young and stupid and scared,” he said. “I’m not anymore.”

He pulled a small velvet box from his pocket and opened it. The ring inside was simple and beautiful—an oval diamond, thin gold band. Understated. Like them.

“Julia Rossi,” he said, his voice rough, “will you marry me?”

She covered her mouth with her hand and nodded so hard her scarf slipped.

“Yes,” she said. “Of course yes.”

They were married a month later in the hospital chapel—wooden pews, stained glass windows, a faint smell of old incense. It wasn’t the wedding either of them had imagined at twenty‑three. It was better.

It was real.

The guest list was small: me, Thomas Beck, Dr. Hill, a handful of nurses who had seen my mother at her worst and gotten her to her best.

My mother wore a simple white dress someone had ordered online and altered at home. Adrien wore a dark suit. Their hands—both left wrists marked with the same rose, the same infinity symbol—were joined as they said their vows.

When the chaplain pronounced them married, the nurses cried. So did I. So did Thomas, though he blamed it on allergies.

Two years later, my mother is still alive.

The cancer is still there, a shadow on scans, a word we never say without also saying “stable” and “managed.” She goes to Sloan Kettering once a month for infusions. The rest of the time, she lives.

Really lives.

She and Adrien bought a house in Connecticut, on a stretch of coastline where the Atlantic looks softer than it does in the city. The house is all gray shingles and white trim, with a wide front porch and rocking chairs that creak just a little when you sit down.

She always wanted to live near the ocean. Now she wakes up to the sound of waves instead of sirens.

They travel when she’s strong enough. Italy, to show Adrien the streets where she played as a kid and the church where her parents got married. Germany, to see the village where he used to sit on a cracked stoop and dream about America. They send me pictures—my mother in a sundress on a cobblestone street, Adrien holding her hand on a bridge over the Rhine.

I went back to NYU.

Adrien paid the tuition. My mother cried the day I walked back onto campus with a backpack and a schedule.

“I knew you would finish,” she said. “You are too stubborn not to.”

I graduated last spring in Washington Square Park, tossed my cap in the air with a hundred other kids whose parents had done everything they could to get them there. I found my mother and Adrien in the crowd—she was in a wide‑brimmed hat and big sunglasses, he was in a suit like he’d come straight from a meeting. They were both crying.

Now I work at a book publisher in Manhattan. I read manuscripts on the subway, reject most of them, and daydream about writing something of my own one day.

Last week, I took the train up to Connecticut for dinner.

The city slowly gave way to suburbs, then to stretches of green and glimpses of water. Adrien picked me up at the station in a car that probably cost more than everything we’d ever owned in Brooklyn put together, but he still drove it like a guy who remembered when one dent would have ruined him.

We grilled fish on the back deck. My mother made a salad the way she used to in our apartment, humming under her breath. After dinner, we sat on the porch with glasses of red wine as the sun slid down over the water, turning the sky gold, then pink, then a deep, soft blue.

The air smelled like salt and cut grass. A breeze lifted the tiny hairs on my arms.

At some point, I looked over and saw their hands.

My mother and Adrien sat side by side, shoulders touching, fingers intertwined on the armrest between them.

The tattoos were visible.

Two roses. Two sets of thorns. Two infinity symbols.

The ink was faded now, almost the same color as their veins. Twenty‑seven years of sun and soap and time had softened the lines.

But they were still there.

“Do you ever regret it?” I asked.

“The tattoo?” Adrien said.

He lifted their joined hands and looked at his wrist.

“I know there used to be… judgment,” he said. “People thinking tattoos meant you were unprofessional. That you weren’t serious.” A faint smile touched his mouth. “I built a multi‑billion‑dollar company with this on my arm. If they judged me, they did it quietly.”

He shook his head.

“I don’t regret it,” he said. “It was the only proof I had for a long time that she was real and not something I dreamed up in a cheap apartment when I was young and hungry and lonely.”

“I kept mine for the same reason,” my mother said. “I thought about covering it, about taking it off. But I could not. It was all I had left of him.”

“And now?” I asked.

“Now,” Adrien said, lacing their fingers tighter, “it reminds me that love doesn’t die. It gets buried. It gets lost. It gets delayed by landlords and bad phone connections and oceans. But if it’s real, it waits.”

My mother squeezed his hand.

“L’amore è bello ma fa male,” she said softly. “Ed è per sempre.”

She looked at me.

“Love is beautiful, but it hurts,” she translated. “And it’s forever.”

“Forever,” Adrien echoed.

They didn’t get a fairy tale.

We still live with scan days and test results and new medications. There are still nights when my mother is too tired to get out of bed, when Adrien sits beside her with his hand around her wrist, his thumb over the rose, his face turned toward the window so she won’t see him cry.

The cancer will probably take her someday.

But not today.

Not yet.

Today, they are on a porch in Connecticut, watching the sky darken over the Atlantic, their matching tattoos visible in the fading light. Today, there is laughter and clinking glasses and the smell of grilled fish still hanging in the air.

Today, they have forever—however long forever turns out to be.

And me?

I have something I didn’t know I was missing until a stranger’s tattoo cracked my life open.

I have a father.

I have the story of how I came to be, not as a half‑told myth about a man from Italy who left but as a messy, painful, beautiful truth about two immigrants who got lost in New York and found their way back to each other.

Have you ever discovered something about your parents’ past that changed everything you thought you knew? Or watched a love story that refused to die, no matter how many years or miles tried to kill it?

If this story about lost love, second chances, and the way one small moment in a Manhattan restaurant can change multiple lives touched your heart, share it with someone who still believes in timing—and in the idea that sometimes, even after decades, the universe finds a way to finish what it started.

Thank you for reading.

News

My husband said, ‘You should move somewhere else to live.’ With no money, I was forced to go to my husband’s company to work as a cleaner to support my children. Until one day, the secretary hurried over and whispered, “Hurry, hide under the desk. You need to hear the truth!”

Serena Hayes dipped her mop into the gray, soapy mess. The water was hot, but her hands had been freezing…

‘She’ll learn a lesson,’ my dad said after leaving my 8-year-old daughter alone at the airport while my entire family flew to Disney. In the family group chat, the message was simply: ‘Come pick her up. We’re about to board.’ My mother added coldly, ‘Don’t make us feel guilty.’ The moment their plane landed…

“She’ll learn a lesson,” my dad said, like he was talking about forgetting a homework assignment and not abandoning…

At my son’s 35th birthday party, he grabbed the microphone and announced in front of everyone: ‘This party was paid for entirely by my future father-in-law, my mother didn’t contribute anything at all.’ I calmly stood up and walked out. That night, I quietly rearranged my entire financial plan, transferring the company I had painstakingly built to someone else. The next morning, when I woke up, I saw… ’76 missed calls.’

My son humiliated me in front of two hundred people by saying I had not even paid for his cake….

This Christmas, my name is not on my family’s guest list. In their eyes, I am just an “invisible” daughter. I quietly booked first-class tickets to take my grandmother to Paris. On Christmas Eve, I calmly informed them and presented the family trust papers that I had rearranged.

This Christmas, I am not on the guest list of my own family. In their eyes, I am still the…

‘Sir, that boy lives with me,’ I said loudly when I saw the portrait in the mansion. I work as a cleaner in New York. I know him!

I clean houses for a living. Not the life I imagined when I left Wyoming for the East Coast with…

‘Move out. You have two days.’ – My parents gave my apartment to my brother right at his engagement party… I used to think my parents truly cared about me, until they publicly gave my apartment to my twin brother – the apartment I had put $30,000 into, which was my entire savings. The moment everyone applauded to congratulate them was also the moment I realized that, for them, everything between us had ended from that day on.

My parents gave my apartment to my brother at his engagement party in a leafy suburb just outside Chicago, without…

End of content

No more pages to load